In July 1983, I was working in a Middle Eastern country. When I heard about the anti-Tamil riots in Sri Lanka, I was aware of a catastrophe, even though I was too politically immature then to grasp the full nature of the tragedy and its implications for Sri Lanka in the years to come. My sympathies for the victims were heartfelt and deep. In 1983, though, I was a very naïve, well-meaning Sinhala Buddhist young man who believed that a limited war could contain the LTTE, and that the government was now fully awake to the ugly reality of communal violence and would make sure it would not happen again by offering the Tamils a satisfactory political deal. Twenty eight years later, I know better. Let’s not start another round of blame games. Whatever terrorists do, governments are duty bound to protect their citizens. What I failed to realise back then was that the government shouldn’t have let Black July happen in the first place. After returning home in 1984, I remember telling a Tamil tenant in my neighbourhood how bad I felt about the whole thing. He didn’t even smile.

In July 1983, I was working in a Middle Eastern country. When I heard about the anti-Tamil riots in Sri Lanka, I was aware of a catastrophe, even though I was too politically immature then to grasp the full nature of the tragedy and its implications for Sri Lanka in the years to come. My sympathies for the victims were heartfelt and deep. In 1983, though, I was a very naïve, well-meaning Sinhala Buddhist young man who believed that a limited war could contain the LTTE, and that the government was now fully awake to the ugly reality of communal violence and would make sure it would not happen again by offering the Tamils a satisfactory political deal. Twenty eight years later, I know better. Let’s not start another round of blame games. Whatever terrorists do, governments are duty bound to protect their citizens. What I failed to realise back then was that the government shouldn’t have let Black July happen in the first place. After returning home in 1984, I remember telling a Tamil tenant in my neighbourhood how bad I felt about the whole thing. He didn’t even smile.

Giving me a blank look, he quickly disappeared indoors. I felt puzzled then by his behaviour, though now I know that, in his place, I would have done exactly the same thing. But I belonged to the majority, brought up with centrist, conservative political views, well-meaning but complacent, and hardly in a position to put myself in the lot of a persecuted minority, of someone who has had a family member hacked to death and the house burnt down by a ranting mob. Now I know better. Even though I was never politically connected to any group that could even be remotely called subversive, and lived in the relative safety of central Colombo during the dark years of the 1987-90 terror and disappearances, I learnt then what it was like to be caught up helplessly between warring factions bent on annihilating each other, what it was like to have a friend abducted and disappeared by a death squad (who turned out to be policemen working for presidential security). I learned the hard way that the locked doors of your own house provided no safety if someone has your name in their list purely by mistake as part of a personal vendetta. There was a period of relative complacency in the 1990s, when Chandrika Kumaratunge became president, vowing to deliver peace and prosperity. Now we all know better.

Especially over the past six years, I have again lived with that lurking fear in the guts, mainly because of my profession of journalism because the grey areas which always existed in freedom of expression have become so murky as to be unfathomable. Being a member of the majority is no longer an insurance policy against wanton personal destruction at the hands of others. That has been my political education over the past thirty years. You are safe as long as you toe the line, but only just so.

When I returned to my home in Colombo Eight in 1984, Borella town and its environs still bore many scars of July 1983. There were gutted houses and buildings along Cotta Road and many of the narrow lanes with whimsical names from the colonial days. The biggest scar was the gutted BCC building with its stricken clock facing Borella town centre.

This building was one of the first to be torched by the mob heading from the General Cemetary (or Kanatta, where the cremation of thirteen soldiers killed by the LTTE in Jaffna sparked off the riots (in reality, not a spontaneous burst of anger but a well-planned ‘pogrom’ involving several top ministers to rid Colombo of its Tamils) towards Maradana through Borella town. The clock bore mute testimony to the tragic hour for many years. Incredibly, no one thought of removing it right into the newmillennium, until the building was finally repainted a few years ago and the old scar of the stricken clock finally removed.

I think that is a perfect symbol of the majority’s insensitivity towards the horrible events of July 1983, of our inability to learn lasting lessons from it. Of the millions who passed Borella town in the intervening years, I wonder how many knew what that clock signified. The symptoms of the malaise are evident when you talk to long-time residents and shop keepers of Borella. Talking to me, none of them has ever mentioned this horrific event, let alone express any regrets.

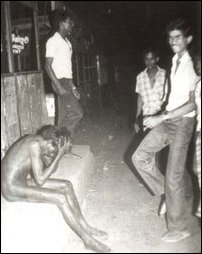

Then there is the Borella bus stand, another eyesore in an irritatingly bland town without any pretensions to culture (the Punchi theatre down Cotta Road looks like a happy accident). Shared uneasily between the private bus mafia and the decadent state bus service, this rundown bus passenger terminal was the infamous venue of a famous photograph taken in July 1983 – that of a naked Tamil man sitting on the cement step leading to it, covering his face with both hands, while a smiling Sinhala patriot is about to kick him viciously.

This is a remarkable photograph because, as far as I know, no other such bleak photographic evidence of man’s inhumanity to man during Black July exists. Pictures only showed gutted buildings and vehicles. This is because photographers themselves were prime targets of the mobs, and inconspicuous devices such as mobile phone cameras were unknown. This black and white photo was taken in fading light with a flash gun.The man who took it was Chandragupta Amarasinghe, an obscure photographer working for the Communist Party newspaper Aththa at the time. No one seems to remember him today. Though his photograph has been reprinted many times (though not in the mainstream media), I have never seen him given credit in print.I remember him as a young man with a scraggly beard who went in slippers, carrying his battered old SLR camera in a ragged cloth bag. It may he his sorry appearance which spared him the mob’s wrath. No one knows his wherabouts today, but his unique, brave photograph is as powerful in its own way as Francisco Goya’s famous painting of Napoleon’s soldiers executing Spanish civilians in Madrid or any of those photographs from the days of civil rights struggles in the US or apartheid in South Africa.

But can we be sure that this dark history won’t repeat itself?

Courtesy: http://transcurrents.com/news-views/archives/2414#more-2414

Sent by : Visagaperumal vasanthan <visagaperumal_vasanthan@yahoo.co.uk>