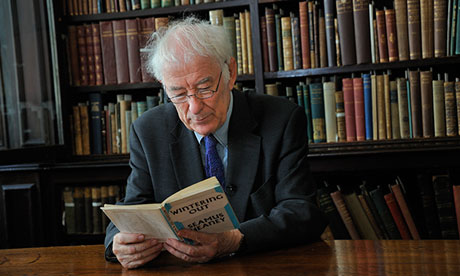

In a time of burnings and bombings Heaney used poetry to offer an alternative world; he gave example by his seriousness, his honesty, his thoughtfulness, his generosity Two years ago I invited Seamus Heaney to read at the Kilkenny arts festival in Ireland. The venue was St Canice’s Cathedral, one of the most beautiful churches in Ireland. It was here almost 40 years earlier that, as a young poet, he had met Robert Lowell, who had become a friend and a mentor. Heaney admired Lowell’s utter dedication to his craft, his ability to change, his absolute belief in the importance of poetry. When I suggested that Dennis O’Driscoll, who had done a book of interviews with Heaney, should introduce him on stage, Seamus said he would like that, but he would prefer it if Dennis would read as well. Dennis, he said, had done enough introducing; since he was also a poet, he should get equal billing. It was typical of Seamus’s generosity. That evening, I suggested to him that he should do no signing of books after the reading, but go and have a drink with the theatre director Peter Brook, who was in Kilkenny and wanted to meet him. As we left by a side door and walked away from the church, he sighed and said that all his life after readings when everyone else was free to walk out into the world, he would spent an hour or more signing books and meeting people. He was the most tactful and careful and scrupulous of men. He used a deep-rooted conscientiousness in his work, but it also came across every time you met him. He had a way of holding back, watching every word, weighing the moment. In his public readings he had a real command; privately, he was almost shy, always thoughtful.

In a time of burnings and bombings Heaney used poetry to offer an alternative world; he gave example by his seriousness, his honesty, his thoughtfulness, his generosity Two years ago I invited Seamus Heaney to read at the Kilkenny arts festival in Ireland. The venue was St Canice’s Cathedral, one of the most beautiful churches in Ireland. It was here almost 40 years earlier that, as a young poet, he had met Robert Lowell, who had become a friend and a mentor. Heaney admired Lowell’s utter dedication to his craft, his ability to change, his absolute belief in the importance of poetry. When I suggested that Dennis O’Driscoll, who had done a book of interviews with Heaney, should introduce him on stage, Seamus said he would like that, but he would prefer it if Dennis would read as well. Dennis, he said, had done enough introducing; since he was also a poet, he should get equal billing. It was typical of Seamus’s generosity. That evening, I suggested to him that he should do no signing of books after the reading, but go and have a drink with the theatre director Peter Brook, who was in Kilkenny and wanted to meet him. As we left by a side door and walked away from the church, he sighed and said that all his life after readings when everyone else was free to walk out into the world, he would spent an hour or more signing books and meeting people. He was the most tactful and careful and scrupulous of men. He used a deep-rooted conscientiousness in his work, but it also came across every time you met him. He had a way of holding back, watching every word, weighing the moment. In his public readings he had a real command; privately, he was almost shy, always thoughtful.

Good morning, and thank you for coming. As is customary at the end of official missions such as this, I would like to make some observations concerning the human rights situation in the country. During my seven-day visit, I have held discussions with President Mahinda Rajapaksa, and senior members of the Government. These included the Ministers of External Affairs, Justice, Economic Development, National Languages and Social Integration, Youth Affairs and the Minister of Plantations Industries who is also Special Envoy to the President on Human Rights, as well as the Secretary of Defence. I also met the Chief Justice, Attorney-General, Leader of the House of Parliament and the Permanent Secretary to the President, who is head of the taskforce appointed to monitor the implementation of the report of the Lessons Learned and Reconciliation Commission (LLRC). I had discussions with politicians who are not part of the current Government, namely the Leader of the Opposition and the leader of the Tamil National Alliance; in addition I met with the National Human Rights Commission, and a total of eight different gatherings of human rights defenders and civil society organizations in Colombo, Jaffna and Trincomalee. I also received briefings from the Governors and other senior officials in the Northern and Eastern Provinces.

Good morning, and thank you for coming. As is customary at the end of official missions such as this, I would like to make some observations concerning the human rights situation in the country. During my seven-day visit, I have held discussions with President Mahinda Rajapaksa, and senior members of the Government. These included the Ministers of External Affairs, Justice, Economic Development, National Languages and Social Integration, Youth Affairs and the Minister of Plantations Industries who is also Special Envoy to the President on Human Rights, as well as the Secretary of Defence. I also met the Chief Justice, Attorney-General, Leader of the House of Parliament and the Permanent Secretary to the President, who is head of the taskforce appointed to monitor the implementation of the report of the Lessons Learned and Reconciliation Commission (LLRC). I had discussions with politicians who are not part of the current Government, namely the Leader of the Opposition and the leader of the Tamil National Alliance; in addition I met with the National Human Rights Commission, and a total of eight different gatherings of human rights defenders and civil society organizations in Colombo, Jaffna and Trincomalee. I also received briefings from the Governors and other senior officials in the Northern and Eastern Provinces.

படைப்புக்களைப் பத்திரிகைகளுக்கு அனுப்பி வைத்துவிட்டு, ‘பெருமானே, பிரசுரமாகுமா? ஆகாதா?’ எனப் பிரார்த்தித்துக் கொண்டிருந்தவர்களை – சேர்த்து அனுப்பிவைத்த தபாற் தலைகளுடன் திரும்பிவந்த படைப்புக்களால் மனமுடைந்து சோர்ந்து போனவர்களை – பெண்டாட்டியின் தாலியை அடகு வைத்துப் புத்தகம் போட்டவர்களை – பெருமனம் படைத்த பிரசுராலயங்கள் வாரிச் சுருட்டியதால் வங்குரோத்தானவர்களை – படிப்பாரற்றுப் பரணில் தூங்கி அடைகாக்கும், கன்னிகழியாக் கதை, கவிதைப் புத்தகாசிரியர்களை – கக்கத்துள் அல்லது கைப்பைக்குள் சுருட்டிக் கட்டி வைத்துக்கொண்டு காண்போர், கதைப்போரின் கைகளுக்குள் தம் புத்தகங்களைப் பலவந்தமாய்த் திணித்தவர்களை – இப்படியாக, எண்ணிலா ‘இம்சைகள்’ தந்தும், தாங்கியும் வந்த தமிழ் எழுத்தாளர்களைப் பற்றியெல்லாம் இன்னுமின்னும் சொல்லிக்கொண்டே போகலாம். கடுதாசியிலான புத்தகங்கள் புழக்கத்திற்கு வந்த காலத் ‘துயர்காதைப் புராணங்கள்’ இவை.

படைப்புக்களைப் பத்திரிகைகளுக்கு அனுப்பி வைத்துவிட்டு, ‘பெருமானே, பிரசுரமாகுமா? ஆகாதா?’ எனப் பிரார்த்தித்துக் கொண்டிருந்தவர்களை – சேர்த்து அனுப்பிவைத்த தபாற் தலைகளுடன் திரும்பிவந்த படைப்புக்களால் மனமுடைந்து சோர்ந்து போனவர்களை – பெண்டாட்டியின் தாலியை அடகு வைத்துப் புத்தகம் போட்டவர்களை – பெருமனம் படைத்த பிரசுராலயங்கள் வாரிச் சுருட்டியதால் வங்குரோத்தானவர்களை – படிப்பாரற்றுப் பரணில் தூங்கி அடைகாக்கும், கன்னிகழியாக் கதை, கவிதைப் புத்தகாசிரியர்களை – கக்கத்துள் அல்லது கைப்பைக்குள் சுருட்டிக் கட்டி வைத்துக்கொண்டு காண்போர், கதைப்போரின் கைகளுக்குள் தம் புத்தகங்களைப் பலவந்தமாய்த் திணித்தவர்களை – இப்படியாக, எண்ணிலா ‘இம்சைகள்’ தந்தும், தாங்கியும் வந்த தமிழ் எழுத்தாளர்களைப் பற்றியெல்லாம் இன்னுமின்னும் சொல்லிக்கொண்டே போகலாம். கடுதாசியிலான புத்தகங்கள் புழக்கத்திற்கு வந்த காலத் ‘துயர்காதைப் புராணங்கள்’ இவை.